Colonial Period

The Colonial Period in Southeast Asia, from the 16th to mid-20th century, was a transformative era that profoundly impacted the region’s cultural and artistic landscapes. Colonisation by European powers such as the Spanish, Dutch, British, and French introduced Western artistic traditions and techniques, alongside which indigenous practices took place laying the way for hybridised art forms. Abacus Art’s portfolio delves into these intricate dynamics, showcasing works that illuminate the convergence of cultural identities, the critique and adoption of colonial narratives, and the evolution of Southeast Asia�’s artistic heritage.

Colonial art in Southeast Asia often served a dual purpose: a tool of colonial propaganda and a medium of local resistance, two very juxtaposing sides. European colonists integrated academic art traditions such as naturalistic painting, portraiture, and religious iconography, which were recognised as foreign to the region’s indigenous artistic heritage. These traditions were realized through landscapes, seascapes, and portraits that depicted the local environment and people through a Eurocentric lens: they catered to the European market's fascination with exotic destinations, illustrating vibrant scenes of native landscapes and budding colonies in a distant part of the world. In the Straits Settlements, modern day Singapore and Malaysia, British colonial rule (1819–1963) shaped local art through Western styles and techniques, reflecting the tension between Western influence and native resilience. Accounts of the East, be it through paintings, photographs or writings, whilst informative, have still been to a certain extent coloured by the preconceptions and reverie of Western travellers.1

As a thriving regional entrepôt, Singapore played a key role as a bridge along major East-West trade routes. Prior to Stamford Raffles’s arrival to the island, Singapura as it was once known, consisted of a diverse flow of people and ideas, this included the Malays, Chinese, Arabs and Indians, connecting to wider geopolitical currents.2

In both Singapore and Malaysia, British colonial governance introduced European academic art traditions through art schools and exhibitions, yet local artists began to combine their own cultural identities through the integration of indigenous traditions and nationalist themes, creating a fusion of local and Western artistic practices.

For instance, the "Artist and Empire" exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore examined the British Empire's complex and contested nature through art. The exhibition featured works from various regions, including Singapore and Malaysia, highlighting how local artists adapted and responded to colonial influences. This showcase underscored the intertwined artistic developments and shared histories of the two regions during the colonial era. ‘Artist and Empire: (En)countering Colonial Legacies’ was showcased for the first time in the United Kingdom at Tate Britain. The exhibition had been mounted to examine the topic of Empire through the lens of art.3

In 2016 colleagues at the National Gallery reshaped it for Singapore with new loans from British collections and other lenders, including artists. This is the first partnership between the Gallery and Tate. Unlike the Tate Britain show, the Singapore exhibition juxtaposed such historical works with those by contemporary artists as well. Contemporary Malaysian artists such as Wong Hoy Cheong and Yee I-Lann, along with Singaporean artists Erika Tan, Lee Wen, and Tang Da Wu, have showcased works that offer alternative perspectives on colonialism.4

Artistic exchanges between Singapore and Malaysia were fluid, with works produced in one territory often influencing the other. This interconnectedness of cultures and artistic practices helped shape a shared colonial art history, where Western influences were both absorbed and resisted in a complex, evolving artistic landscape.

This interplay between colonial perspectives and local cultures was not unique to Singapore but extended across Southeast Asia, influencing how the region was represented in Western art. The painter Rudolph Bonnet was highly regarded in his day. At an exhibition of his works held in 1931 in Semarang nearly every piece was sold. The Belgian Adrien Jean Le Mayeur de Merpres, who settled in Bali in 1932, was also commercially successful.The extraordinary beauty of his wife, the famous temple dancer Ni Pollok contributed greatly. He was an expert at exploiting the myth of the unspoilt paradise full of mysterious and sensuous women that was Bali.5

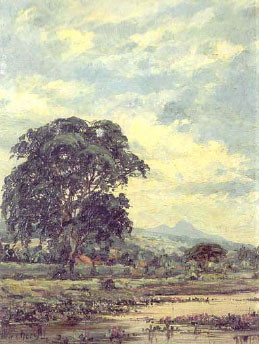

During this period, artists both European and local, produced works which depict romanticised versions of the region’s landscapes and cultures. Local artists adopted and adapted these Western visuals and techniques, resulting in a unique visual language which addressed colonial realities while preserving their cultural identities. Filipino artist, Ancheta Isidro (b. 1882 - 1946) trained in fine art at Ateneo de Manila. He was a painter that captured the local landscapes and sceneries of the Philippines. His romantic paintings captured the traditions of the country using Western techniques of realism. He often depicted seascapes, rice fields and villagers at work. These works would also serve as documentation of the region under colonial rule.

Lucien Frits Ohl (1904-1976) was a Dutch-Indonesian artist known for his impressionistic and romantic depictions of life in Southeast Asia. His works often featured idyllic kampong scenes, lush scenery and landscapes. The painting Woman with Child at Kampong Gate depicts a village gate dressed in vibrant colours, with a peaceful nostalgic atmosphere. This work reflects the European fascination with the “exotic” and ‘oriental’ qualities seen in the native population, untouched by modernity or colonial influence. This allure led to many romanticised depictions of Southeast Asia, constructing an idealised, picturesque image of life in the colonies. Although this painting may not be a reflection of daily life, it was an attempt at capturing the essence of the ‘native’ way of living palatable to a foreign audience.

Soedibio (b. Madiun, Indonesia, 1912 - 1981) was an nonconformist Indonesian artist known for his abstract works. He was a member of the PERSAGI group of revolutionary artists, PERSAGI is the acronym for Persatuan Ahli-Ahli Gambar Indonesia (Union of Indonesian Painters). The artists of PERSAGI saw themselves as cultural workers within the nascent nation-state of Indonesia, making them part of a broad socialist-nationalist front aimed at the creation of a new national consciousness out of the inheritance of a colonial past. PERSAGI, was a historic movement in Modernist Indonesian Art spearheaded by the artist Soedjojono. Between 1938 and 1943 the association had about twenty members including Affandi and even later on a younger Hendra Gunawan. Their work often displays highly emotional, dominant themes of struggle for independence, poverty, and injustice in the first half of the 20th century.

The Abacus Art collection includes the work of artist Soedibio, who incorporated a distinctive visual language that made a significant impact on the development of Indonesian art in the 20th century, his career unfolded during a transitional period in the early colonial years. His practice explores themes of the human condition, often integrating traditional Indonesian elements with modern influences. He was highly influenced by Javanese mysticism and decoration, particularly his large body of paintings of figures from wayang, traditional shadow puppetry.

Vietnam has historically been influenced by its neighbours and colonists, including China, which occupied parts of Vietnam over 2,000 years ago, and more recently France, which colonised Indochina from 1858 to 1954. While Chinese artistic influence in Vietnam has been pervasive for millenia, the French influence in Vietnamese art, and particularly painting, can be traced back specifically to the creation of L’Ecole des Beaux Arts de l’Indochine in Hanoi in 1925 by a classmate of Henri Matisse, Victor Tardieu. Many prominent artists mastered European techniques and media to express traditional Asian subjects and ideas, thus creating a new and distinctive style.

In 1931, Victor Tardieu, sensitive to the talent of the young Vietnamese artist, made him his assistant for the Paris Colonial Exhibition. For Lê Phó, this stay was an opportunity to discover both France and Europe. His travels through countries as varied as Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium, as well as his visits to museums - where he admired the Primitives, referring to the early European painters, particularly from the Gothic and early Renaissance periods (14th–15th centuries)- led him to deepen his knowledge of Western art and to confront it directly. His palette was traditional, sober and composed of dark tones. While Asian and European influences are evident in his work, universal codes are also often present in accessories such as the lotus flower, fan, and the scarf. Lê Phổ continued to perfect his brushwork over the years. His discovery of the Impressionists in France around 1940 brought to his work a colorful, joyful palette that is absent from his first period. His palette was enriched by vivid colors and the use of more western supports, such as canvas, soon facilitated the introduction of oil paint, giving way to a vibrant, innovative execution. In the later stages his floral paintings became some of his most recognizable works, yellow, orange, red, green and pink vibrant flower compositions. Encouraged by his full possession of the medium, Lê Phổ revisits the classic composition of the still life.

Colonial-era artistic interactions were more than just an assertion of Western influence, they also fostered a dynamic fusion of styles, allowing Vietnamese artists to reinterpret their cultural identity by blending traditional techniques with modern innovations.

After 1945, Vietnamese artists, like the rest of the population, struggled with the immense hardships brought on by decades of war. Artists, who often serve as witnesses to this history, found themselves documenting and utilising art in navigating the harsh realities of war, while trying to preserve and evolve their cultural identity.

The art of the Colonial Period in Southeast Asia reveals a rich tapestry of cultural exchange, resilience, and innovation. As colonial rule persisted, art became an important medium for resisting and critiquing colonial power. In places like Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, nationalist movements were gaining ground in the early 20th century, and art was used as a tool to express resistance against colonial dominance. Local artists began to emphasize indigenous subjects, motifs, and narratives that had been suppressed or ignored by colonial authorities. Artmaking became a key tool for addressing the aftermath of colonial rule, often dealing with themes of trauma, migration, displacement, and identity crisis, ultimately shaping the trajectory for the modern art period. The notion of what it meant to be "postcolonial" was not fixed and was constantly evolving.

By curating these works, AbacusArt provides a nuanced exploration of colonial-era Southeast Asian art, bridging the historical and contemporary. Art during this time was not merely a reflection of European influence but an active, dynamic response to it. Iconic artworks and historical artifacts reflect the creativity of Southeast Asian artists who, in various contexts, created lasting works that celebrated their cultural identities and engaged with the influences of colonialism. This dialogue between history and creativity makes Abacus Art’s engagement with the Colonial Period an essential lens for understanding Southeast Asia’s artistic legacy.